The Kalash: An Endangered Culture in Hindu Kush

By Mubina Parveen

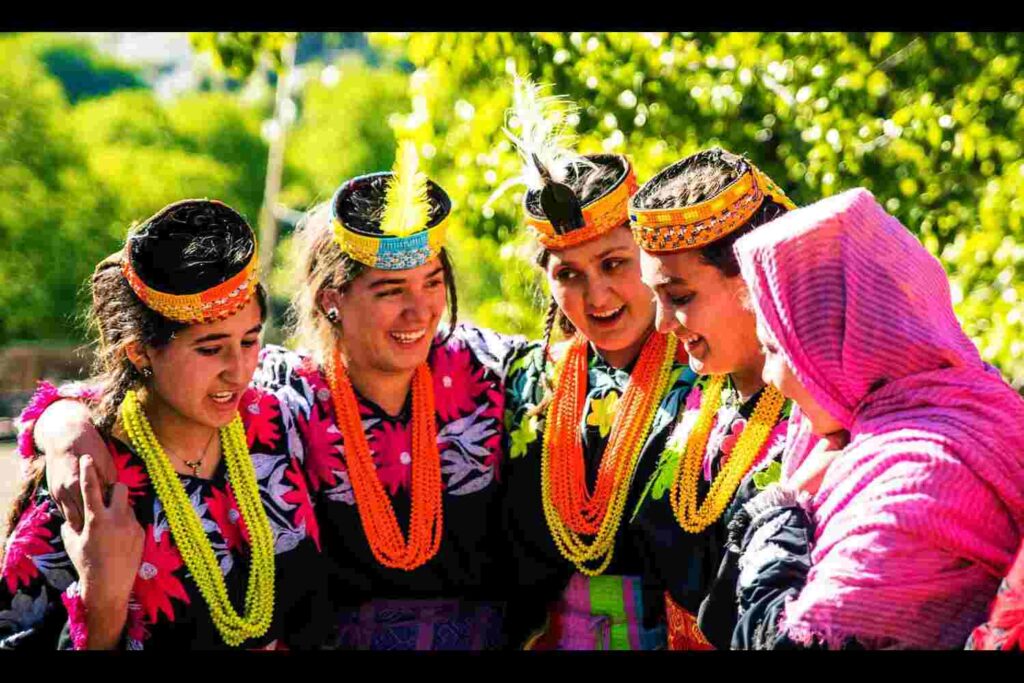

The Kalash are an isolated South Asian population of Indo-European speakers dwelling in the Hindu Kush mountain valleys in the northwestern part of Pakistan, close to the Afghanistan border. They represent a religious minority with novel and rich cultural practices which recognize them from the encompassing population. As their number is continually shrinking, numbering only about 4,000, their unique culture is in danger of extinction.

Kalash Origin Theories

The Kalasha community of Chitral district has long charmed the imagination of both the visitors and researchers. Yet, one angle that to date evades and confounds historians and archaeologists is their origin. Beginning with the previously well-known and now discarded narrative of their descent from Alexander the Great’s Macedonian troops, different theories have been advanced to explain the enigmatic identity of the Kalasha. For instance, a large number of the Kalash are fair-skinned and blue or green-eyed, and these features add to the well-established legend that they are for sure relatives of Greek soldiers who battled close by Alexander the great in Pakistan around the year 300 B.C. A genetic study conducted in 2015 tracked down no proof to help the theory of their descent from the soldiers of Alexander.

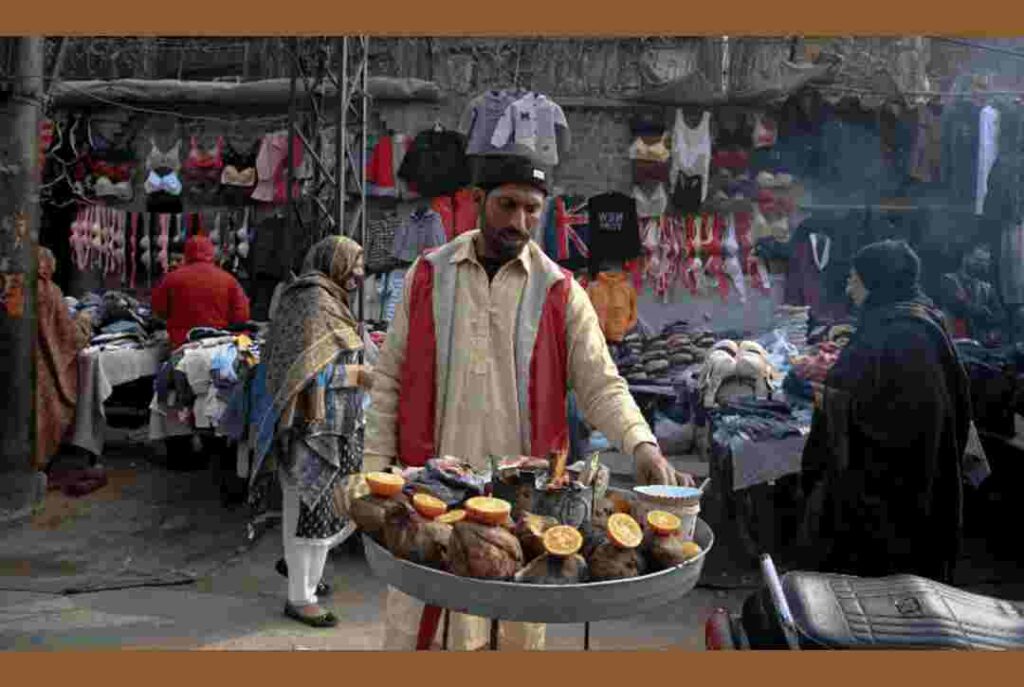

Kalash Culture and Geography

Geographic Distribution

The Kalash people are found to be staying in three valleys of the Hindu Kush: Rumbur, Bumburet, and Birir in the Chitral district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The Rumbur and Bumburet grouping form a single culture because of likenesses in their cultural practices, while the Birir grouping, being the most traditional one of the three, shapes its very own different culture. The region is at the junction of what is known as the Nuristan area of Afghanistan in the west, Swat and Gilgit in the east, Pamir knot in the north, and Lowari Pass in the south. The Kalash language is supposed to be part of the Dardic group of Indo-Aryan languages.

UNESCO and Language

According to UNESCO, the language is listed as being critically imperiled, as like numerous other tribal languages everywhere, Kalash has no proper script. On its part, even the Government of Pakistan has put forth no effort to document and keep a record of this unique language. What is far worse is that till date there doesn’t exist a single standard text devoted solely to this culture.

Religious Practices and Festivals

In terms of religious practices, the major deities worshipped by the Kalash people are: Sajigor, Mahandeo, Balumain, Dezalik, Ingaw, and Jestak. As far as strict practices, the significant divinities venerated by the Kalash public are: Sajigor, Mahandeo, Balumain, Dezalik, Ingaw, and Jestak. Two sorts of religious events portray Kalash society. The first kind might be viewed as religious as well as ceremonial with singing and dancing, while the subsequent kind might be perceived as being purely religious with no such merrymaking. Their significant festivals include: Joshi, Chaumos, Uchal, and Pul/Poh.

Historical Context

Kalash in Literature

In Rudyard Kipling’s time, the Kalash were known as the “black Kafirs” or siyah posh (blacked robed) their land was Kafiristan, the setting for his story of insanity and idolatry, The One Who Might be king. The “red Kafirs,” their neighbors, the subjects of Kipling’s story, were severely changed over towards the end of the nineteenth century. They became Nuristanis, “enlightened ones,” and their rugged mountain land is one of the centers of the war against the Taliban.

Formal Recognition

In April 2017, a provincial court in Peshawar formally acknowledged the Kalash community as a separate ethnic and religious group. Chitral-based senior journalist Gul Hamad Farooqi, who has broadly covered every single cultural festival and other important parts of the Kalasha public, says these individuals are ‘Indian Aryans’.

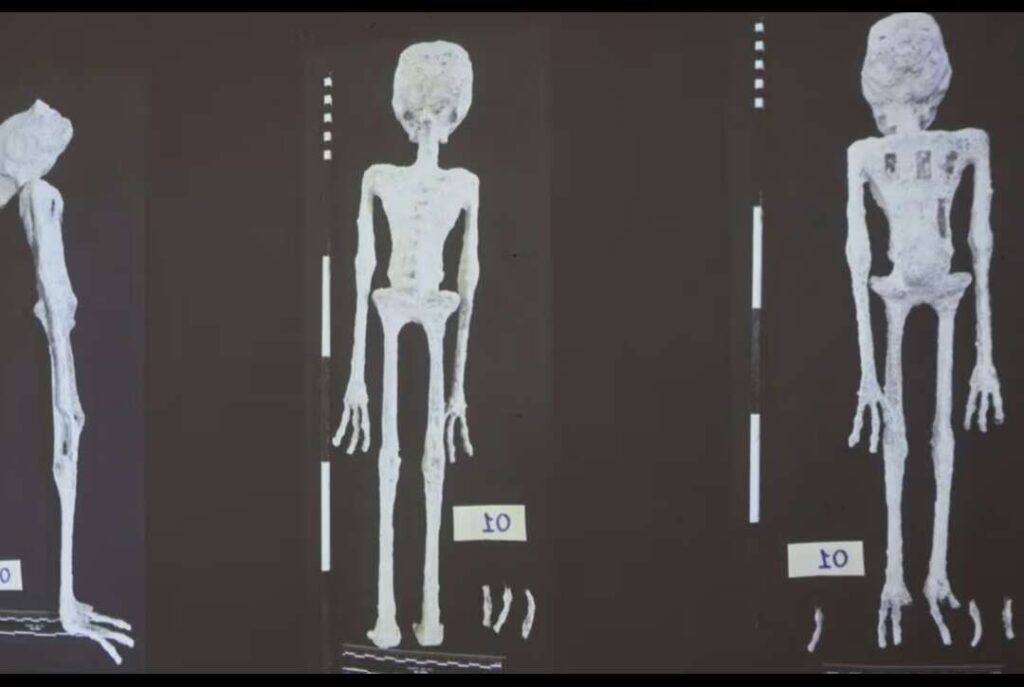

Recent Archeological Discovery

As per Farooqi, the provincial Archeological Division with the help of international archeology experts had recently found a 5,000-year-old graveyard in the Shindor area of Chitral. “The experts in their investigation of the cemetery had expressed that individuals possessing the region are Indian Aryans. Nonetheless, the experts don’t drive the Kalasha community to accept that they are not the descendants of Alexander the great. The Kalasha people take pride in associating themselves with the great conqueror,” he added. People of the Yamnaya culture are accepted to have relocated eastwards and westwards in waves, settling in regions as far separated as South Asia and Great England. Their relocations prompted the expansion of dialects that are classified under the Indo-European language family. In the Indian sub-continent, the Yamnaya migrants are believed to have been among the forefathers of the North Indians’, one of the many ancestral populations the advanced inhabitants of the region are descended from.

Kalash in the Context of South Asian History

Ancestral Population

As indicated by the 2015 study, the Kalash, because of their uniqueness, may have been the earliest group to isolate from the ancestors of the modern population of the subcontinent, sometime around 11,800 years ago.

Ethnic and Sectarian Landscape of Pakistan

Before we go into an intricate analysis of the ongoing situation of the Kalash people, understanding the ethnic and sectarian scenery of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is significant. For quite a while, Pakistan has been known to detest the recognition of different ethnic identities. This in many ways resulted in the making of Bangladesh in 1971 and the different insurgencies that plague the country even to this date. Inside its own fabric, on account of an unwritten policy of ‘othering,’ the country has alienated its minorities be it the Muhajirs, Balochis, Shias, Ahmadis, Ismailis, etc. As depicted above, with a sparse population of 3,000 people, the Kalash are not even 1% of the population; yet the uniqueness of their being and their composite history and heritage increases the value of the immense landmass they belong to, which quite a long time ago was home to Islam as well as Buddhism, Hinduism, and other animistic religions. With this background, the Kalash people can be perceived as being ethnically marginal while comprising a demographically insignificant minority in a country made on the grounds of religion.

Constitution of Pakistan

The Constitution of Pakistan lays out Islam as the state religion, Articles 20-22 rights of freedom of religion and religious education and Articles 26 and 27 forbid discrimination based on religion in relation to access to public places and provision of public services. Regardless of these constitutional safeguards, it is widely known that any open support to forms of exclusiveness, whether linguistic, ethnic or religious, causes much bloodshed within Pakistan.

The Kalash People: A Challenging Reality

Historical Context

Prior to the 1400s, the Kalash were the rulers of lower Chitral. They were initially defeated by the Chagatai khanate and then finally subdued by the Raees, a ruling clan of Badakhshani origin. Living within an Islamic State, pressure to convert to Islam has forever been there on the Kalash and has existed for almost hundreds of years. It is said that the Kalash people had likenesses in tradition and cultural practices with the nearby people of neighboring Nuristan province of Afghanistan. Moreover, this region was known as Kafiristan, the place where the Kafir live. The Kalash who live today in the valleys of Hindu Kush are the last survivors among people of Kafiristan, a region that once enveloped the whole northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan before the region was divided by the Durand Line, the border established between Afghanistan and British India in the 19th century. It is believed that in 1895 Amir (Ruler) Abdur Rahman Khan, the king of Afghanistan, vanquished the region and forced the inhabitants to convert to Islam. Known as the “Iron Amir,” he proceeded to name the region Nuristan, or the “land of celestial light.” Around this time, the Kalash were severely vanquished; their ancient temples and wooden idols were destroyed; their women were forced to burn their folk costumes and wear the burqa or veil, and scores of people were converted at sword point to Islam. Fifty years later, two Kalash valleys of Jinjeret kuh and Urtsun had to embrace Islam. Nonetheless, three remaining valleys could be saved from this oppression, obviously on the grounds that the Ruler of Chitral liked to involve them as slaves in the way they existed. Nevertheless, as per records, over the past few decades, almost 50% of the total population in Kalash has converted to Islam.

Recent Challenges

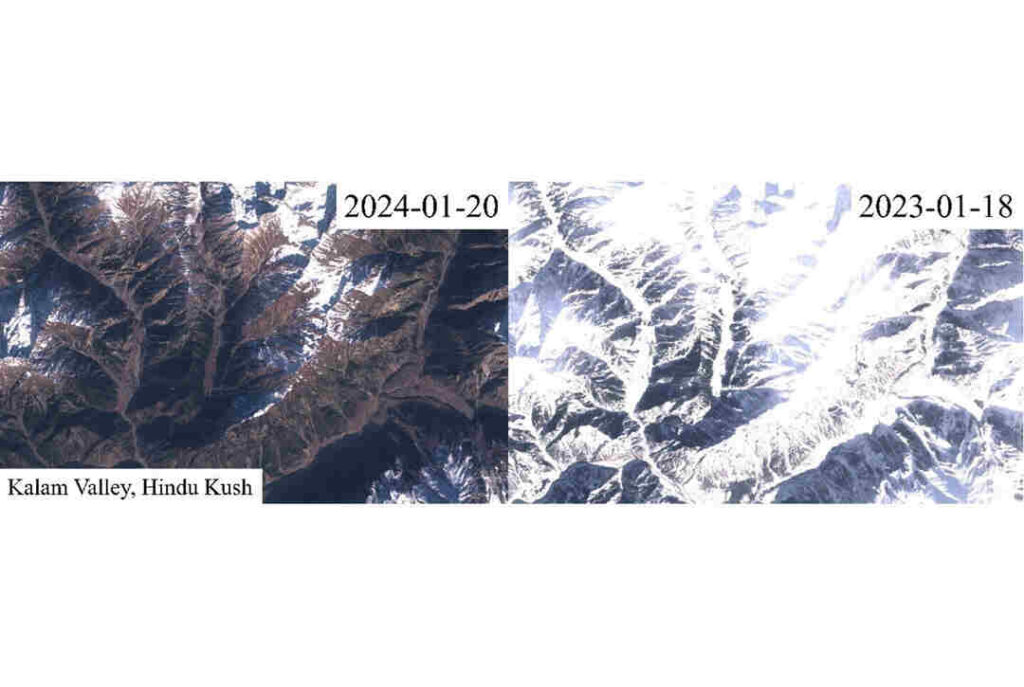

Post 9/11 the situation has been very tense for the Kalash, resulting in an existential crisis. Following US operations in the neighboring Nuristan province of Afghanistan, scores of Taliban militants were rushed out into the district of Chitral, causing enormous threat to the locals. In 2009, a Taliban unit stole into the valleys at night and kidnapped Lerounis. They had been warned by local people thoughtful to their objective and came to the Kalasha Dur during a night when just two security guards were posted. Lerounis was taken quickly across the Afghan boundary to Nuristan. Lerounis, who needs to return to the valleys, lets me know he would rather not discuss the kidnapping in light of the fact that doing so would endanger the Kalash people. Whatever they think of the Taliban’s policies, the Kalash stress their neutrality: they are too vulnerable to court trouble. The Afghan refugee and the Pathan Tablighi parties seized almost 70% of their property during the period, 1981 to 1995. The first impact of the Afghanistan jihad for the Kalash was the pulverization of their forests and wildlife by the refugees. As the vegetation developed inadequate, their dairy cattle met a similar destiny as their forests, and the traditional Kalash means of livelihood were irreparably destroyed.

Issues of Kalash

- Government schools in the valley: With the obvious pretext of imparting education to children and mainstreaming them, the schools in the area it is claimed have been trying to alienate the young pupils from the Kalash way of life. By emphasizing just on the teachings of Allah in Arabic, a sense of inferiority is overall purposely soaked up among these students in regards to their own religion. The marginal improvement caused because of education in these three valleys in a way is at the expense of risk to their indigenous non-Islamic culture. The elderly people in the community have expressed worry that the advent of modern lifestyle and the younger generation’s proximity to Islamic way of life and teachings (when they go to school) are likely to usher in many irreversible changes which could potentially wipe out their uniqueness so carefully preserved.

- The absence of a proper road: The absence of a proper road to link the valleys to the rest of the country has throughout the long term deterred neighborhood and foreign tourists to appear in huge numbers at their annual festivals. It likewise makes it tremendously challenging for the community to transport patients to hospitals in Chitral for treatment during medical emergencies. However in 2017, the Lowari Passage, connecting Chitral, where the Kalash live, to the region of Upper Dir was officially inaugurated, the Kalash themselves, however, hardly get any benefit from related businesses as these enterprises are largely controlled by non-Kalash people.

Danger the community is experiencing

Ironically, the Pakistani establishment often uses these colorfully dressed tribal people to demonstrate the country’s diversity, but invests nothing in them. This is in sharp contrast to their not so beautiful truth of oppression and discrimination in the hands of the majority community. Today the Kalash people face huge pressure from encompassing Islamic communities who are continually pushing towards Islamization of the three valleys inhabiting this tribe. That, combined with the fact that the valleys are in a region where the Pakistani government has de-facto no control, makes the fate of the old culture of the Kalash obscure. As the Kalash do not believe in divine books and messengers, ‘their disbelief’ makes them kafir or infidels according to the predominant Muslim community.

In 1992, a study led by Institute for Current World Affairs determined the dangers implied in the presence of a separate animist Kalash character in the valleys possessed by them. It states how local non-Kalash people, both Muslims and Christian missionaries put financial pressure and provide incentives to these people for religious conversion. Christian evangelists have additionally lured the individual Kalash families with electricity and stipends for the children. The poor economic conditions of these people are likewise utilized as a tool for conversion in exchange for jobs. Activists and researchers likewise note that the Kalash settlements are quickly encompassed by a growing Muslim population as over the years the community has lost control over large parts of their lands through sale or mortgage. Accordingly, socio-economic deprivation is a significant variable responsible for the community’s decline. This issue has its sociological impacts driving Kalash women to marry outside the community. Increasingly, it seems Kalash women marry non-Kalash men with the stated intention of having a better life, and eventually, the women convert to Islam, giving up their original way of life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Kalash people represent a unique and endangered culture in the Hindu Kush mountains. Their origins remain a subject of debate, and their historical context is marked by challenges and conversion pressures. The community faces numerous issues, including threats from the Taliban, the impact of government schools, and socio-economic challenges.

It is imperative to recognize the importance of safeguarding the Kalash culture and heritage. Their distinct language, religious practices, and festivals are part of a rich tapestry that contributes to the diversity of the region. Efforts should be made to preserve their unique way of life and protect them from conversion pressures.

The Kalash people’s story serves as a reminder of the need to protect and celebrate cultural diversity in a world where such diversity is increasingly at risk.

English

English